Religion and Climate Change at the ESA Midterm Conference

The ESA Midterm Conference in Tilburg

On 20–21 August 2025, Tilburg University hosted the Midterm Conference of the European Sociological Association’s Research Network 34: Sociology of Religion. With the theme “The Liquid Presence of Religion in the Public Sphere,” the conference brought together international scholars to explore the shifting and dynamic role of religion in contemporary societies.

Among the diverse sessions, Panel Session 12 on “Climate Change, Environmentalism, and Political Theology” drew significant attention. This panel examined how religious ideas and vocabularies continue to shape responses to ecological crises, even within highly secular contexts. Two presentations from Tilburg University scholars — Caroline Vander Stichele and Ömer Gürlesin — offered compelling insights into the intersections of climate discourse, religion, and media.

Caroline Vander Stichele: The End is Nearer – Apocalypse and Climate Change

Caroline Vander Stichele’s presentation, titled “The End is Nearer: Apocalypse and Climate Change,” analyzed how apocalyptic language and imagery are mobilized in contemporary climate activism.

She demonstrated how Dutch climate groups — including Scientist Rebellion Netherlands and Fridays for Future Nederland — deploy apocalyptic rhetoric to frame the urgency of the ecological crisis. Phrases such as “ringing the alarm bell,” “a rapidly closing window of opportunity,” and “no time to lose” echo the structure of traditional apocalyptic narratives, where humanity is confronted with imminent catastrophe and forced to choose between destruction and survival.

Vander Stichele also highlighted the multimedia strategies used to amplify these messages. Activist campaigns frequently combine text, visuals, and sound to communicate urgency: images of wildfires and floods, Doomsday Clock symbolism set minutes before midnight, and ominous music tracks in online videos. These elements function much like modern apocalyptic prophecy — only here, the prophets are scientists rather than religious figures.

Her concluding observations emphasized that while the religious authority of scripture or divine revelation is absent, science itself has assumed a revelatory role. Apocalyptic discourse has not disappeared in secular societies; it has been reframed. In the climate arena, scientific warnings operate as revelations of hidden truths, pressing society toward immediate collective action.

Ömer Gürlesin: Dogma, Doctrine, and Data – Science as a Religious Construct in Climate Discourse

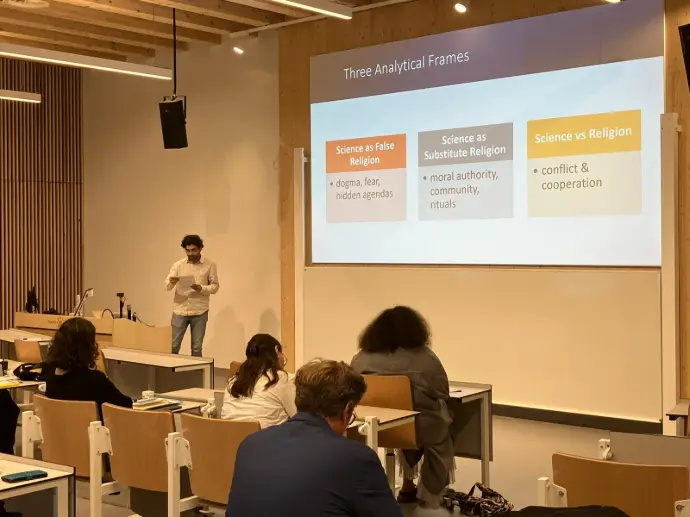

In the same panel, Ömer Gürlesin presented “Dogma, Doctrine, and Data: Science as a Religious Construct in Climate Discourse.” His paper explored how public debates on climate science in the Netherlands often unfold in religious terms.

Drawing on a dataset of 30,000 Dutch-language tweets from 2023, Gürlesin identified three dominant frames in the online discourse:

-

Science as a Substitute for Religion

Here, science assumes the role of moral authority and community-building. Calls to “listen to the science” or “trust the science” resemble religious exhortations, transforming empirical findings into moral imperatives. Activist groups, such as Extinction Rebellion, even perform symbolic actions — like blindfolding statues — that dramatize scientific warnings in ritualistic form. -

Science as a False Religion

In contrast, critics frequently dismiss climate science as dogma, labeling it a “climate church” with its own “priests” and “holy texts.” The Dutch term klimaatreligie (“climate religion”) recurred throughout the dataset, often tied to accusations of hysteria, manipulation, or political agendas. In this frame, climate science is rejected not because of data but because it is perceived as authoritarian belief. -

Science vs. Religion

Surprisingly, the Dutch case showed little direct antagonism between science and organized religion. Instead, churches often appeared alongside scientists and NGOs in coalitions for climate justice, framing ecological responsibility in terms of both stewardship and evidence. This suggests that, far from a culture war, Dutch discourse allows for moments of cooperation between science and faith traditions.

In his conclusion, Gürlesin argued that these frames illustrate the fluid boundaries between religious and secular vocabularies in today’s climate debates. Science can be sanctified as a substitute for faith, condemned as dogma, or partnered with religious communities in shared activism. This dynamic interplay demonstrates how deeply symbolic resources shape public engagement with the climate crisis.

Complementary Perspectives

Although their approaches differed, Vander Stichele and Gürlesin’s presentations converged on a key insight: climate discourse in the Netherlands is never purely secular.

- Vander Stichele traced how apocalyptic motifs — once grounded in scripture — now reappear through scientific authority and activist media.

- Gürlesin showed how science itself is framed in quasi-religious terms, either as sacred truth, false dogma, or a partner in moral action.

Together, these contributions underscore how religious vocabularies remain central in shaping how society imagines ecological threats and responsibilities. Climate change, in this view, is not only an environmental or political challenge but also a symbolic and cultural one.

The ESA Midterm Conference in Tilburg highlighted the continuing importance of religion in public life, especially in relation to urgent global issues such as climate change. These insights remind us that public responses to climate change are shaped not only by facts and policies but also by narratives of fear, hope, and ultimate meaning. Whether through the language of apocalypse or the sacralization of science, religious vocabularies continue to influence how societies perceive, debate, and act upon the climate crisis.